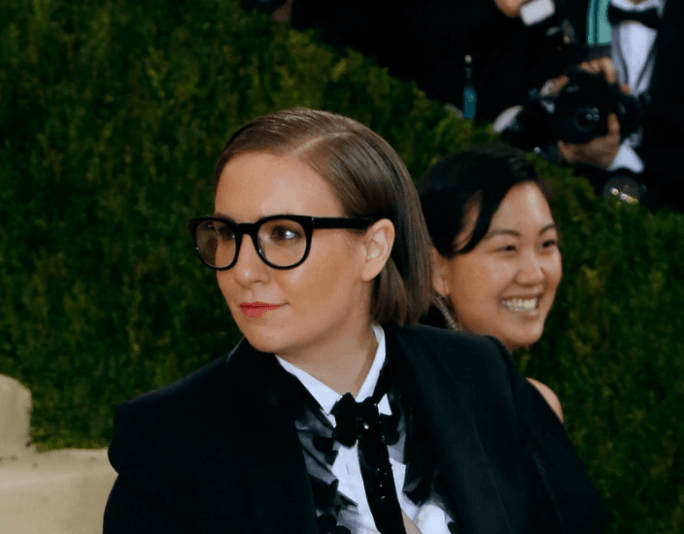

The creator of Girls published an essay this week on why she apologizes so much, and why it's so hard to stop. It's not enough to believe in ourselves, we actually have to consciously break the habit.

It's hard to pick a track off Beyoncé's Lemonade, but lots of people go with "Sorry." This is "partially because it's catchy as f**k," writes Lena in her essay—on LinkedIn, of all places—"but also because it allowed women to express…just how sick to death they were of apologizing."

is part confession, part advice column, part throw-down—and all great. "Apologizing is a modern plague," writes Lena. "So many of the women I know apologize like it’s a job they were given by the government."

I like that she articulates all our (very, very many) sorries as a problem of habit, not of confidence. I happen to apologize a lot. I also happen to completely believe in myself. And these two things converge at weird times, usually when I'm grappling with the unfamiliar feeling of owning power. At my old job, I once had to train a new person. I don't think I've ever said sorry so many times: for showing them the bathroom, for running through the schedule—for presuming I could possibly have knowledge and experience to pass on.

For Lena, this was at 24, when her series was suddenly front and center of, well, a lot of things. "I felt an acute and dangerous mix of total confidence and the worst imposter syndrome imaginable," she writes. She found herself apologizing, all the time, for everything. It got so bad that her dad set her a challenge: to spend a week not saying sorry.

This, as I can imagine too well, left a bunch of gaps in her conversations. "But what do you replace sorry with?" she asks. "Well for starters, you can replace it with an actual expression of your needs and desires." Spoiler: this a really, really effective and lovely way to communicate. Much better than sorry.

Sorry is a good thing, in the right place. Like…well, like a lot of things. "One of the most important things a person in charge can do is own their mistakes and apologize sincerely and specifically, in a way that shows their colleagues they have learned and they will do better," writes Lena. Word.

But you have to use it wisely. When you say sorry, the other person immediately takes it as a given you've done something wrong: at work, at home, wherever. They accept (or not) your apology, even if you actually haven't done anything. After an especially gruesome break-up, I once apologized to an ex for letting him cheat on me for so long—which, it's worth mentioning, I'd had no idea about. "That's okay," he said. "You've had such a busy year."

If this was a Choose Your Own Adventure, I'd just go back, and steal a line from Lena's essay: "Sorry you had to be mean."

We need to quit our daily sorry fix, and save apologies for special occasions. "When I replaced apologies with more fully formed and honest sentiments, a world of communication possibilities opened up to me," Lena writes. "I'm just sorry it took me so long."

instant happy in your

mailbox every day.